I watched the film Searching for Sugar Man last night, and was so struck by the Christ-figure imagery that I felt I had to write about it.

The film is about a man named Sixto Rodriguez who is offered a recording contract in the early 70's, but never makes it as a musician to the surprise of the music industry. He's later dropped from the label, but his music takes off in South Africa. His songs become the voice of the oppressed in the war against apartheid, influencing new music, and leading to government censorship. Eventually Rodriguez is hunted down and found after decades of obscurity.

The film portrays Rodriguez as a very simple man who has worked hard all his life, and goes through great suffering as his royalties got lost in the corrupt record label system.

It struck me that this suffering character is reminiscent of Christ, who was dead for 3 days, while Rodriguez was assumed dead for 30 years. Both men come across as extremely humble, and extremely simple. Both had jobs as manual labourers, and Rodriguez' daughter even describes Rodriguez as a carpenter.

In both cases the system plays a part. The Roman system 'washed their hands' of Jesus' murder, while everyone in the music industry claimed to have been abiding by the royalties scheme and thus are blameless.

One writer in the film even titles his search of Rodriguez as 'Searching for Jesus', because Rodriguez puts Jesus as his first name, rather than Sixto, on some songs.

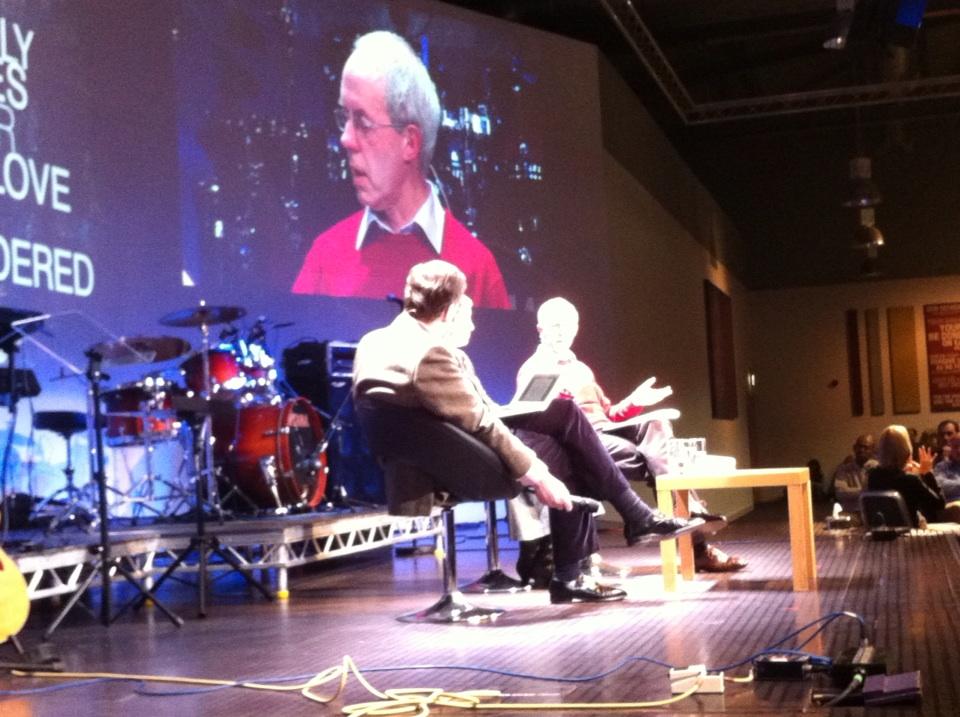

What struck me most however, was the effect of the resurrection in each case. Rodriguez played a series of gigs in South Africa to vast crowds, all of whom are overwhelmed at this man's existence, and many having doubted the reality of his being alive up to the moment before he came on stage. The recordings show people completely captivated and singing with their eyes closed and hands in the air; scenes reminiscent of Hillsong!

Worshipers in a Hillsong Church. Similar scenes to

Rodriguez' gigs in South Africa.

It made me think that while Jesus' resurrection appearances were to 500 people max, when he comes again the atmosphere will be even more electric and overwhelming. The man who has been forgotten, rejected, and stripped of his due royalties, will be given all that he is owed and much more.

What is fascinating, however, is that Rodriguez returns to the USA, rather than staying in South Africa. In the same way, after the resurrection Jesus returns home. The difference of course, is that Rodriguez has returned to South Africa several times since then, while Christians wait for the next and last return of Jesus.

There are also many other differences between the two men (one being the nature of each man's message), but certainly there are some interesting parallels, such that have made me see the second coming in a new light.

We now live as South Africans who have searched for, and found, Jesus; yet we await his return to South Africa to come and live with us forever. In the meantime there are plenty of gigs and parties to attend in celebration of having found him, and we await the 'great gig in the sky', as Pink Floyd put it.

Interestingly the metaphor could be flipped, and Rodriguez could be a prodigal son figure, but that might be a theme to keep in mind for re-watching the film.

As far as the film goes I thoroughly recommend it!