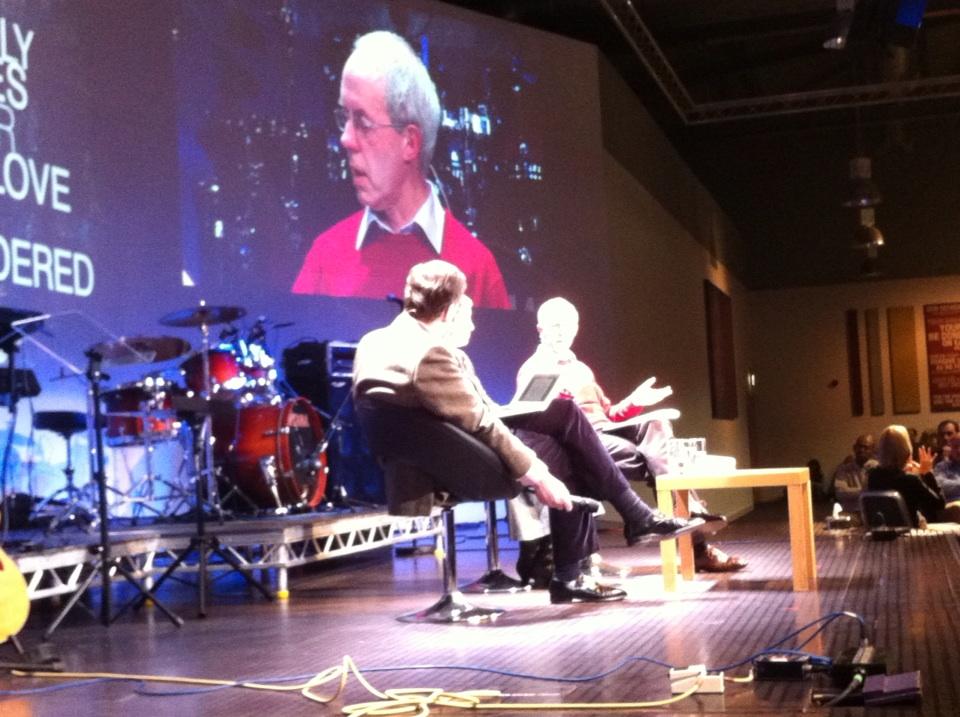

Justin and Caroline Welby are interviewed by John Mumford at Trent Vineyard Nottingham on Sun 27th Jan 2013. Image tweeted by John Wright (@CJohn_Wright).

It

was a real pleasure to see the soon-to-be ArchBishop speak again. I first saw

him speak at a youth conference on evangelism in Durham, and funnily

enough his talk ('sermon' according to John Mumford) was the same; though

clearly more developed! Nevertheless, he spoke with wisdom and clarity (as

before), and I felt confident that he will make a good ArchBishop, even if he

seemed to think the appointing didn't make sense! I would argue that there is

great strength in Welby's detachment from the stifling academic environment

(not to suggest that he is in any way unlearned, as he is clearly a very

intelligent man), and that comes from someone who currently intends to go into

academia! The tendency for academics to get lost in their own minds is

such an obvious stereotype, and one that I see in myself! Therefore my readers have my permission to let

me know if I ever encase myself in an ivory tower.[1]

I hope that Welby will forgive my paraphrase of his talk, as I am writing from

notes and memory rather than a recording.

Welby opened his talk with the assertion that the idols of this

present age have fallen one after another; the financial crisis, the integrity

of the media and politicians, the health system, the list goes on. He argued

that today’s society is disillusioned with the present state, and that when

everything fails only an empty cross and an empty tomb is left standing; thus Christ was the focal point of his talk. Because of this, now is the time for the church

to be a light in the darkness, now is the time for social action and integrity,

for genuine relationships with the person Jesus.

But how can the church go about this? Welby had five points all beginning with P;

Peace: Christians are to bring peace following

Jesus’ example in Lk 24:36 and Jn 20:19. When the disciples are scared and

lost because their world has crumbled around them, Jesus’ answer is to bless

them with peace.

Presence: Like a certain monastic community in France, Christians are to affect change in the areas where they live.

Christians should be present in difficult situations, and the positive change they bring

should be evident.

Promise: When idols are falling there is a lot of

cynicism and mockery. Christians should remember that God is faithful and true

to his promises. In times of doubt we should be seeking the Spirit for

affirmation of God’s love and constancy.

Purpose: The church must fill the gap left by state-run social programs that have lost their funding. A sense of purpose is

important in times of uncertainty. Furthermore, social action will lead to

opportunities to share the gospel, and every Christian should be able to

explain the good news if such an opportunity occurs. Education was an example.

Power: The power that God gives us is always equal

to the task that he calls us to do. In the Holy Spirit, God’s power takes

control of the space left by broken idols.

Welby, like Dallas Willard in his fantastic book The Divine Conspiracy, was incredibly practical,

something that is often forgotten for the more favoured spending ones “time in nothing but telling or

hearing something new” (Acts 17:21).[2]

The spiritual disciplines of prayer, reading the bible, fasting, and studying

the bible (reading commentaries) all made an appearance, and there could have been others that I didn’t notice. Furthermore, practical evangelism was

stressed, specifically; social action, practicing summarising the gospel, and

having spiritual conversations.

Generally, all this made for a thoroughly

enjoyable evening, from Caroline Welby’s intense description of their struggle

with God’s will, to John Mumford’s comic interview technique. I appreciated the sense of church unity shown through the hosts Trent Vineyard, and I wish Justin and Caroline all the best as they step into this new role. I pray that God might keep them close to him and equipped in the power of the Holy Spirit.